#

6:45 a.m. Driving up the turnpike from Brunswick to Bangor, headed down east to Mount Desert Island, I’m apprehensive. I’m returning to what I’ve always called my “other life”: different marriage, different house, different job, different hobbies, different self. A self, quite frankly, I’ve never liked very much.

But I’ve received an invitation to attend the 50th high school reunion of the Mount Desert Island Class of 1974. For many of these students, I was their English teacher as well as senior class advisor. And while I have, at best, mixed feelings about this other life, I enjoyed teaching at MDIHS and have continued to be in contact with some of these former students. I’d really like to see them.

The reunion is tomorrow, but besides an invitation to the reunion, I’ve been asked to talk about my book, The Geriatric Pilgrim: Tales from the Journey at a gathering—which I figure will mostly be former students— in Bar Harbor a few hours from now. So, while I watch the leaves change color as I drive north, I try to figure out what I’m going to say.

I know I’ll start by saying the most important thing I learned in writing The Geriatric Pilgrim was that the physical pilgrimages Mary Lee and I made to places like Iona, Big Sur and the redwoods, Nova Scotia, Israel, Africa, and Turkey have shown me that any journey—including the one we make as we age (and these former students are now all pushing 70. Good God!)—can be a pilgrimage. Especially if looked at with curiosity and openness, as explorations to discover new facets of ourselves, seeking surprises rather than security, looking for evidence of and trusting in a power greater than ourselves.

Then, I think, Okay, if any journey can be a pilgrimage, that means this trip back into my other life is a pilgrimage. How?

When Mary Lee (who is sitting beside me, looking at a map of Maine—she loves those big unfolding maps that take up half the front seat) have gone on a pilgrimage, we often talk about what new insights we’re bringing back with us which we can use in the future. So, what lessons did I learn during the seventeen years I spent at MDIHS that have stayed with me?

Well, I’ve always said that those years were the best teaching years of my life. I’ve taught in other schools, some with more impressive teachers, some with smarter students, some with better sports programs, a wider variety of extracurricular activities, more opportunities for materially or intellectually challenged students. But what made MDIHS different was that, despite the annual arguments about the budget and the tensions about dress codes and what was being taught, the parents, the school board, the administration, the faculty, and the students all agreed on one thing: MDIHS was a good school. And because we all thought it was a good school, it was—winning national awards for excellence.

Making a pit stop at the rest area outside of Bangor, I realize how I frame the reality of my life determines how I see that reality, which in turn determines how I live that reality. Thinking we had a good school, I went to work each day excited and proud to be there (okay, not every day, but I can honestly say, most days) which made me work harder, which made me a better teacher and the students better students. Fifty years later, when I can think of my aging not as a problem, but as an opportunity for growth, I’m less anxious about what I can no longer do and more curious about finding new things I can do, more grateful for those things, which makes me more pleasant to be around.

Back in the car, however, turning on to Route 1A and heading for the coast, I ask: if MDIHS was such a great place to teach, why did I leave, and in the middle of the school year? What’s the lesson there?

It probably begins with that guy I used to be—the one I’ve never liked. Come to think of it, he didn’t like himself either. Despite the accolades (one state evaluator said my Advanced Placement English class rivaled the one at Phillips Exeter), I was not a happy camper. I’d created this persona—loud sports coats, matching ties and pocket handkerchiefs, green ink corrections symbols and sarcastic comments in the margins of papers, pictures of sixty-four famous authors glaring down from the walls—which began to feel like a body bag.

Soon after waking up one morning gasping for breath as if someone had their hands around my throat, I resigned. In the middle of the school year. Moved out of my house, divorced my wife, married another woman, and moved 120 miles away to teach not AP seniors but freshman juvenile delinquents (one of whom as far as I know is still in prison for murder).

And I think the reason I’ve never liked that guy in my other life is that I’ve always thought he was a fraud. But thinking about it, I honestly liked my job, and I wanted to honor my profession by looking and acting my best. I recall reading in David Whyte’s book, Work as a Pilgrimage of Identity, something to the effect that the things which once served us can imprison us if we remain with them too long.

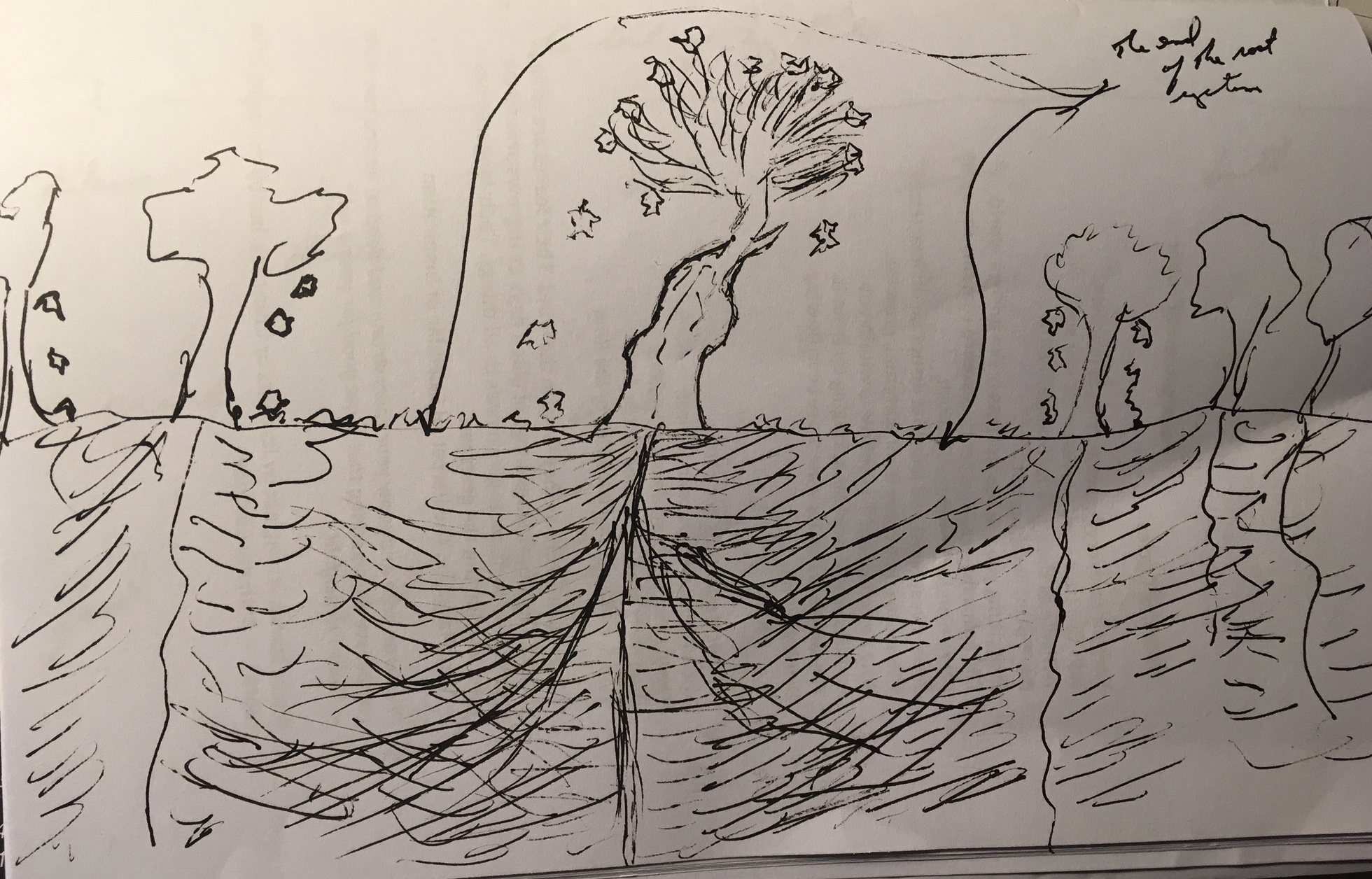

Which, as I think about it, is also true as I age. I can’t hold onto those activities, that self-image, those beliefs that once sustained me. When I think about making a new pilgrimage, I can’t plan—or I shouldn’t, anyway or I’m going to be disappointed, either that or die—to hike the Appalachian Trail or climb Mount Katahdin, but I can continue the journey toward what I might, for lack of a better word, call my true self. A journey, I realize, that began when I left Mount Desert Island, maybe even before.

Speaking of which, I can now see MDI on the horizon, its rocky silhouette reminding me that this is one of the most beautiful places on earth. I remember, especially in those days when most of the tourists went home after Labor Day, how many afternoons and weekends I spent walking the trails and beaches there. And I realize that those walks were the beginning of what I call —somewhat euphemistically perhaps—my spiritual journey. Sitting on the top of one of the mountains, looking out over the neighboring islands, I experienced not only the inchoate presence of a Higher Power, but also a vague sense that everything belongs.

I needed help interpreting these experiences. Which led me to religion. When I first began teaching on the island, I hadn’t been in a church since I was married in one, and by the time I left seventeen years later, I was not only a member of a church but a member of the Board of Deacons. I sang in the church choir. I advised a church youth group.

It dawns on me that without Mount Desert Island, there’d be no Geriatric Pilgrim.

I also see that I have no “other lives,” only this one—one that has been unfolding, like one of Mary Lee’s maps, from the beginning until now and will keep unfolding (I’m guessing; I’m curious to find out) after my earthly death.

Wow! Now, if I can just remember to talk about some of this an hour from now…

# #