#

After years of counseling and going to meetings, remembering Christmas when I was a kid now feels like peering through my frosted window at a soft and steady snow covering up dead leaves, discarded pumpkins, and broken branches under the diseased hemlocks beside the house.

My family’s disease was alcoholism. Mom’s memories of her drunken father passed out on Christmas Day, her shame at not being able to bring friends home, Dad’s bitter memories of Christmases in a Home for Wayward Boys and in the Army during WWII, his sense of being victimized by a social system he saw based on greed—feelings he tried to wash away with a pint of Old Crow—the arrival each Christmas of my mother’s mother, Nanny C, a large bitter woman whose acid tongue could peel paint, permeated our house during the holidays like their cigarette smoke.

In the weeks before Christmas, I’d hear Dad’s grumpy voice through the register in the floor of the bathroom asking where the hell were they going to get the money and Mom’s brittle reply they were just going to have to find a way; her children weren’t going to have the shitty Christmases she did. And I’d know it was up to me to make sure the holidays were happy. So that Christmas morning when Dad groaned because his head hurt, and Mom and Nanny perched on the edge of their chairs hovering like crows on telephone poles watching my younger brother and sister and me open our presents, and I ripped off Christmas wrapping to find a rainbow-colored wool hat that only a girl would wear, I said, “Oh, I love this. Thank you!”

Ah, but here come the snows of nostalgia, which, I’ve discovered, is not all bad, especially when it brings memories of wading up to my knees in in the white stuff to help my father cut a tree, the smell of fresh fir as Mom and Dad set up the tree on the porch, decorating it with ornaments I still have 70 years later, popping corn and stringing it on the tree, smelling Nanny C’s fudge and Mom’s cookies and bread, and hearing my grandmother playing carols on our piano.

Or of walking home from sledding in the 5:00 p.m. darkness, carrying my Flexible Flyer past the drug store and the hardware store, their neon lights shimmering, casting shadows on the snow banks, past the big white Georgian houses on Main Street with their candles in the windows, then down Bridge Street, seeing my house and our lighted tree on the back porch, and feeling the Christmas excitement when the possibilities of happiness were as many as the stars in the frozen sky.

Or of helping my father, who moon-lighted as sexton in our church, get ready for the Christmas service by picking up last week’s bulletins from the Sanctuary, alone in this great empty space, the whistling of my corduroy pants as I walked echoing in a great and holy silence, and somehow feeling safe—held, enfolded by a Great Presence.

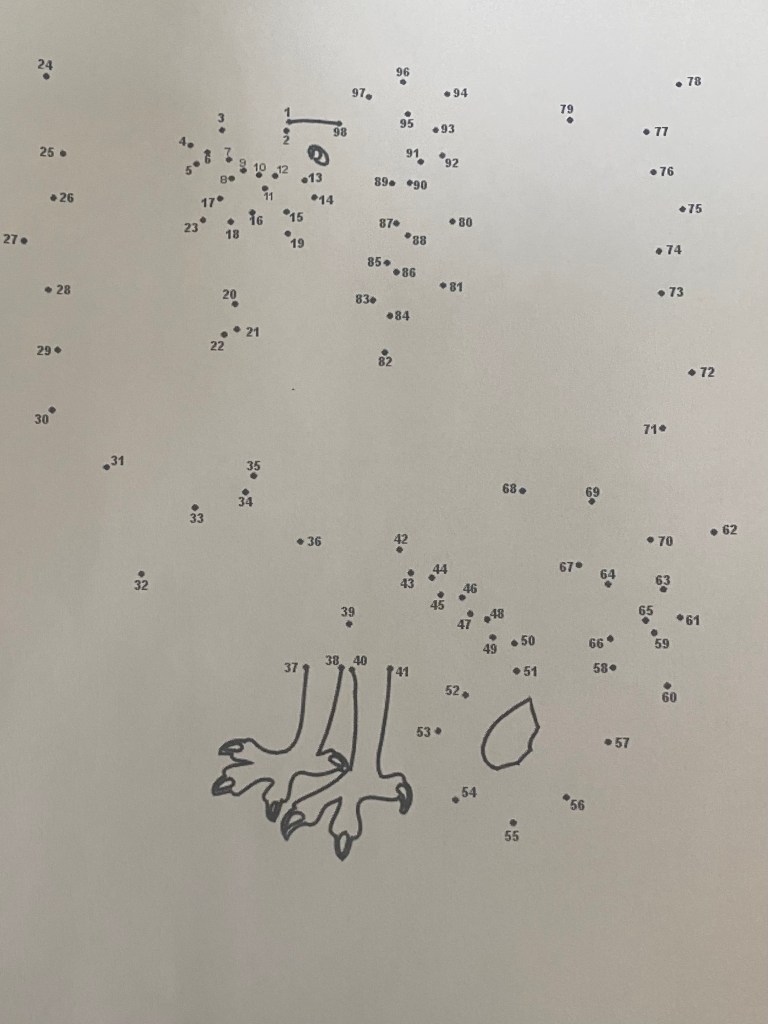

Then Christmas day: giggling in bed with Jaye and Roger, as we wait for 6:00 a.m. when we can wake the grownups, not knowing that Nanny C is in the next room listening to us with tears of joy running down her face—“Oh, you kids are so good, God bless you!” Christmas dinners of turkey, mashed potatoes, gravy, stuffing, homemade bread, and cranberry sauce (which is what I ate. Let the grownups eat the squash and turnips and beans), followed by Mom’s pumpkin, apple, and blueberry pies topped with Sealtest Ice Cream. In the afternoon, Dad slept off his hangover on the couch, Nanny went back to the piano and she and Mom sang “White Christmas,” “The Christmas Song,” “I’ll be Home for Christmas,” while I played with my new model airplane or helped my brother or sister put together their farm or showed them how to play the new Parcheesi game or took my new skates (but, gee, I forgot my new hat) which Mom and Dad had bought on time to the town rink behind the movie theater or went up to my room to read the book I’d received: maybe Treasure Island, Tom Sawyer, Herb Kent West Point Fullback, a Hardy Boy’s mystery, or Zane Gray.

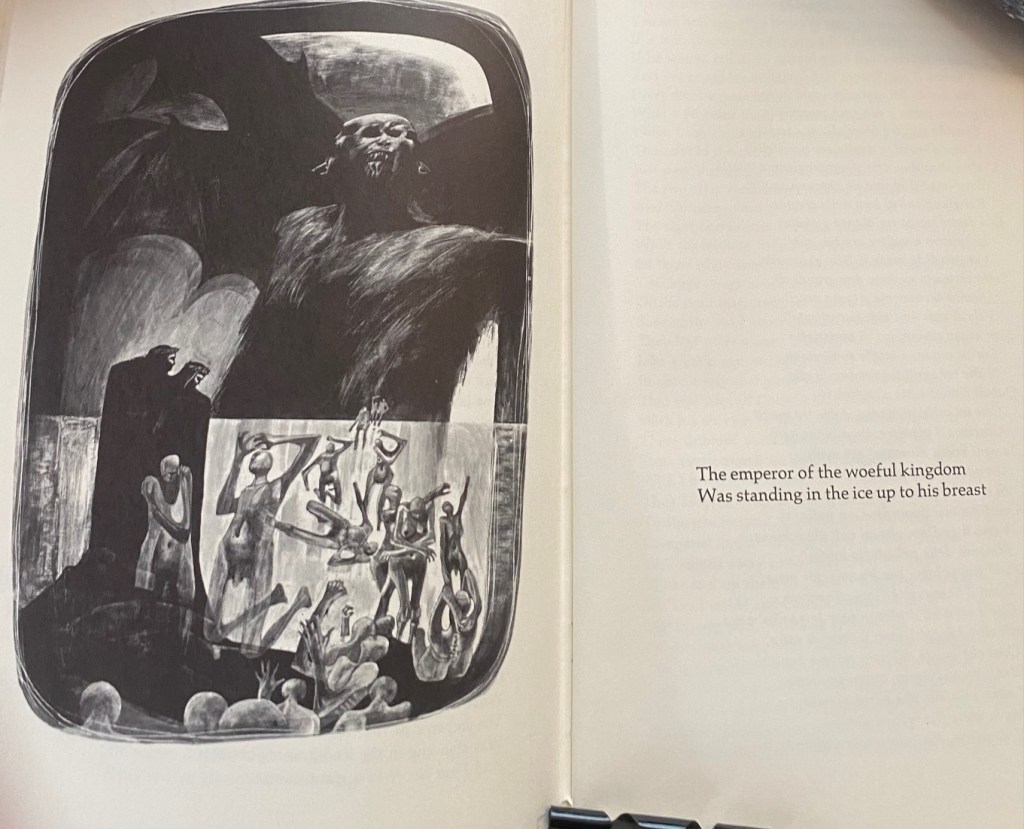

On Christmas night I went to bed with a plate of cookies and a glass of milk, turning on the radio to my favorite programs, most of which were having Christmas specials: Jack Benny exclaiming after having spent the last thirty minutes buying the cheapest gifts he could find, “Good night, everyone, and merry Christmas!” George Burns telling his wife, “Say good night, Gracie,” and her reply, “Good night, Gracie, and Merry Christmas,” and of course, a version of Dicken’s “Christmas Carol,” probably starring Lionel Barrymore. I ate, finished my milk, and crawled completely under the covers with the cookie crumbs, following Scrooge on his journey from “Bah, humbug!” to “God bless us, everyone!”

While outside the window, at least in my memory, snow fell in great white, silent flakes.

# #