#

A few weeks ago, after seeing a doctor about increased soreness in her knee, my wife Mary Lee began a new regimen of physical therapy: quad stretches, hamstring stretches, mini squats, wall sits, looped elastic band hip extensions. These to go with exercises she’s been doing for years to restore movement to her right shoulder. (I like the one where her hands look like frightened spiders scampering up the wall, and another one where she uses a can of Great Northern beans.)

Because I’ve been doing various daily exercises since back surgery in 1977, mornings at the Wile residence resound with creaking bones, tendons rubbing on cartilage, occasional grunts punctuated by yawns and a “meow” or two from our cat, who has taken on the role of personal trainer.

Our bedroom looks a bit like Rick’s Sporting Goods, with two sizes of exercise mats, two sizes of weights (in addition to the can of beans), rubber stretch bands, and folding chairs. A treadmill resides in the guest bedroom across the hall.

Physical therapy after my back fusion was deceptively simple: walk ten miles a day for three months. Every day. Sun, rain, snow, sleet, hail. And since I was operated on at the end of December, I walked through it all. Sometimes in the same day. But you know, I grew to love those walks (Well, Route One got a little boring but at least it was clear after a snowstorm), and I kept walking—maybe not ten miles every day, but often five or six.

Twenty years later, after bi-lateral hip surgery, my physical therapy involved water exercises; walking back and forth for 30-45 minutes in the shallow end of a pool, pool dumb bells, and gloves that made me look and feel like Aqua-Man. But it worked. On a trip to Florida to visit my parents over school vacation, two months after the surgery, Mary Lee pushed me through Newark Airport in a wheelchair to get to our connecting flight. On our return a week later, after spending most of my time walking the swimming pool, I strode through the same airport feeling like Hercules Unchained.

That led to yoga, tai-chi, back to walking, this time with my hiking poles that I named Waldo & Henry (To learn why, go to https://geriatricpilgrim.com/2020/02/07/waldo-and-henry/), which led to the hikes and pilgrimages that became the blog you’re reading.

Flash ahead another twenty years: open heart surgery, and more physical therapy at a rehabilitation center, where three times a week for six weeks, I taped on my heart monitor, rode a stationary bike, walked a treadmill, and lifted weights. When the program ended, I bought the treadmill that sits in the guest bedroom (great for watching TED talks, but I still miss those cute nurses at ReHab) and the weights that I use instead of cans of Great Northern Beans.

But I’m falling apart more quickly these days. Over the last two years I’ve added breathing exercises to help my “moderate” COPD, more stretches to help with the bursitis that seems to have camped out next to both my bionic hips, daily exercises at the computer to ward off Carpel Tunnel and something called Ulna Nerve Entrapment, and weekly sessions with a Feldenkrais instructor.

As Thomas Jefferson said, the price of freedom is eternal vigilance. Or in the words of my old PCP, move it or lose it.

#

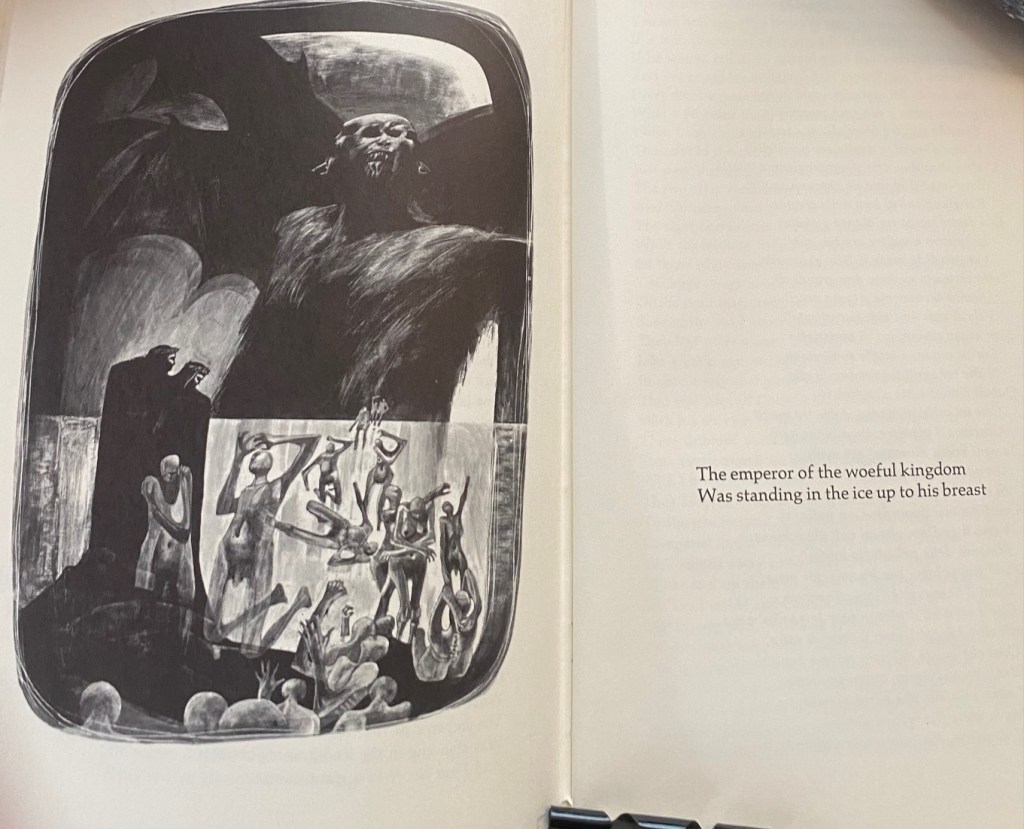

Before Mary Lee and I begin our morning grunting, stretching, creaking, and moaning, we sit in contemplative prayer for twenty minutes, a practice I’ve maintained since my daughter died 35 years ago, when, after raging at God for several years, I decided I needed to listen to what God had to say back. This listening—with my whole body, with all my senses—is what I continue to try to do. As I think about it, this, too, is a kind of physical therapy.

I’m reading a lot these days about quantum physics and spirituality. As I understand it, quantum physics posits that the universe is conscious, if by “conscious,” one means a system that can communicate or process information and then use this information to organize itself (which is what all those protons, neutrons, and electrons that make up the atoms that make up all matter do). So, mind and body aren’t two separate things but rather two aspects of the same cosmic material.

Modern writers about spirituality, such as Richard Rohr, Diana Butler Bass, Phillip Clayton, and Ilia Delio, seem to me to propose that this cosmic material, this “consciousness” that resides within me as well as around me, is the incarnational presence of God. So that in meditation, I am trying, as I am when I do my stretches and lift my weights, to reestablish pathways, strengthen relationship with what 12-steppers call a Higher Power.

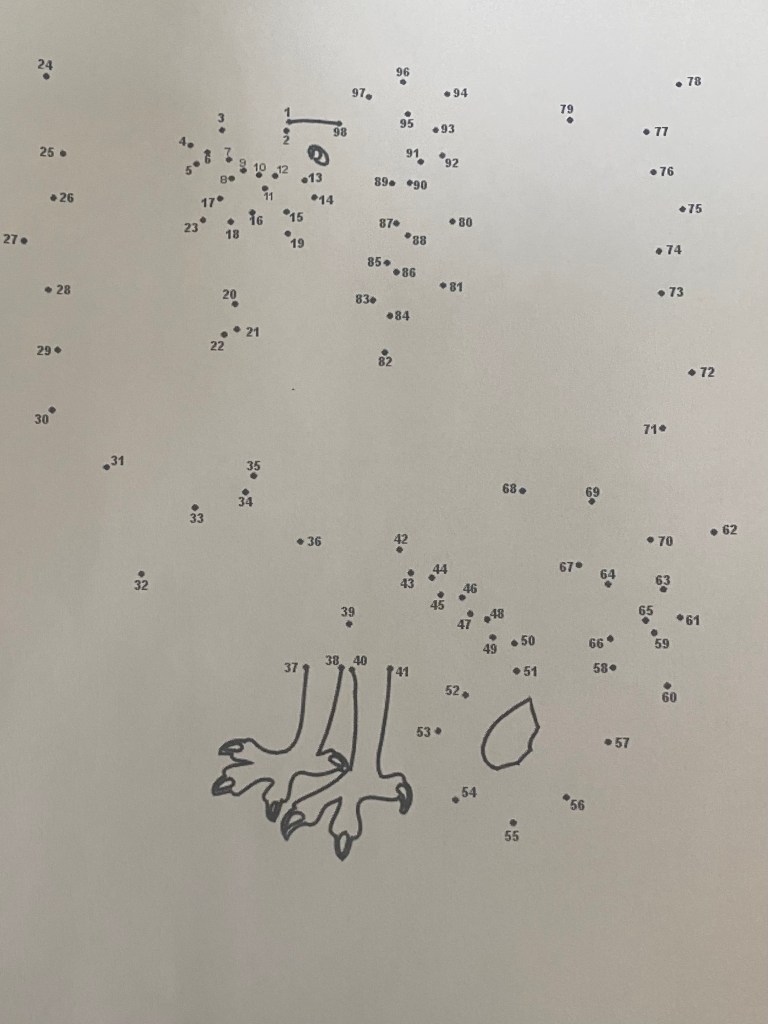

Besides meditation, I do other exercises to strengthen my spiritual muscles. My Feldenkrais sessions, focusing on integrating eyes, head, shoulders, ribs, pelvis, legs, and feet to facilitate ease of movement, remind me that one of the great spiritual lessons is that everything is connected. And that my job—my “exercise,” if you will—is to recognize and facilitate these connections.(And for more about the importance of connecting, go to https://geriatricpilgrim.com/2024/02/01/connecting-the-dots/)

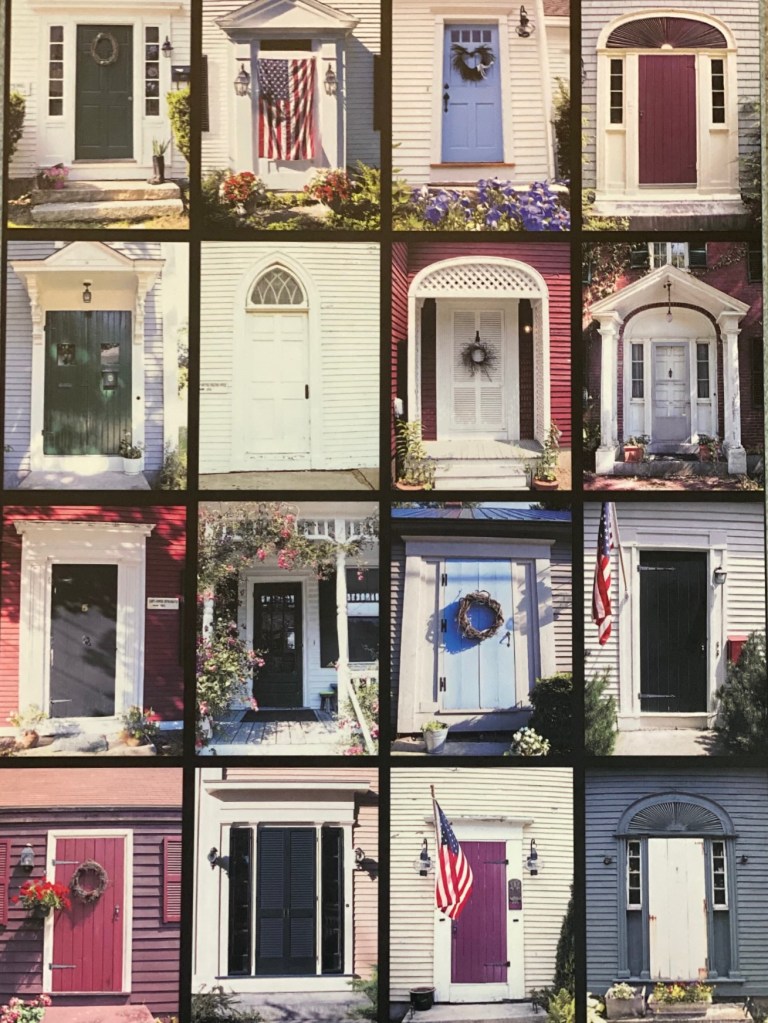

One of my character defects that keeps me from connecting is trying to control everything and everybody. So, at the suggestion of my Al Anon sponsor, I’ve been taking Waldo and Henry for walks without having a destination. When I first started doing this, I felt lost. I walked in circles. But as I persisted, I discovered roads in the neighborhood and paths in the woods I’d never noticed before. Which is leading me to try to approach other activities, such as meetings, book readings, and potential confrontations with family and acquaintances with the same curiosity, trying to surrender presumptions, looking for the sacred in situations I’ve always avoided and spiritual teachers in people I’ve always disliked.

Probably more than anything else, it’s the physical act of writing which connects me with the Sacred. The only way I can even begin to understand concepts such as quantum physics and the ideas of those spiritual writers I’ve mentioned is to first put the ideas down in my own words on a yellow legal pad with my bold-ink pen. I can write second/ third/ fourth/ ad infinitum drafts of my blogs on a computer. I can edit on a computer. But first I need to work those pen and paper muscles.

Of course, the ultimate integration of mind and body (and what I’ve been working my pen and paper muscles on for the last eight-plus years) is the pilgrimage. Last week, a friend sent me a recent article in The Guardian about the increasing numbers of people making pilgrimages. (In the early 1980s, for example, the number of people who walked the Camino de Santiago—the most famous of all pilgrimages—was in the low hundreds; last year, the number was 446,000.) I’m delighted that people are finding that this combination of physical and spiritual activity can be healthy, healing, and holy.

It sure is for me.

# #