#

“Great things are not done by impulse, but by a series of small things brought together.”

—Vincent Van Gogh

#

This blog is a milestone for me. Eight years ago this month, I published my first Geriatric Pilgrim blogs (https://geriatricpilgrim.com/2015/11/). And while I’m not big on party hats and horns, I want to celebrate.

The Romans erected the first stone markers to let travelers know not only the number of miles they had to go to reach their destinations, but also the distances they’d covered. Today, businesses talk about a milestone as something that demonstrates a significant, marked change or step in the development of a project. Parents keep track of milestones in their child’s development. (“Look, little Leslie’s walking! Where’s the camera?”)

When I think of the importance of milestones in my life, I think of the second day of our seven-day walking pilgrimage along St. Cuthbert’s Way through Scotland and England. Still apprehensive about being able to complete the 72-mile trek, I looked back across a newly mown field to the Eildon Hills fading into the dimly distant horizon. The day before, my wife Mary Lee and I had crossed those three hills. I felt a burst of energy. Look at how far we’ve come, I thought. We can do this!

And as I look back at those first blogs from 2015, I’m also surprised and energized by how far I’ve come in the last eight years.

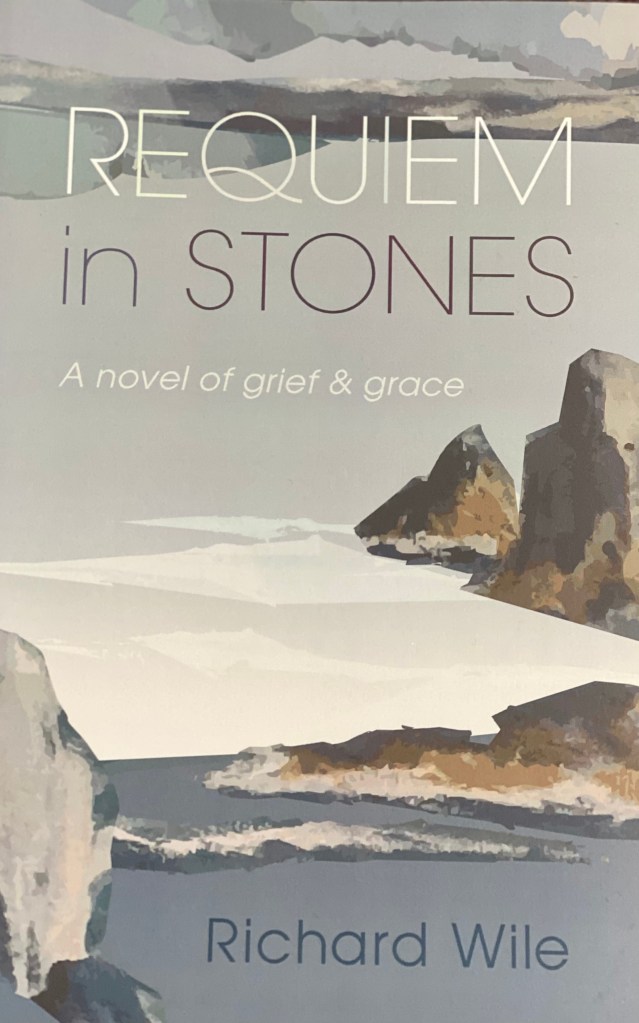

In 2015, I’d just published a novel, Requiem in Stones: A Novel of Grief and Grace, based on my experiences after my daughter Laurie died of cancer.

This novel about the effects of a child’s death upon a family, had taken me 20 years to write and I was emotionally drained. For the sake of my sanity (not to mention the wellbeing of those around me), I wanted to write something for fun.

Two years earlier, Mary Lee and I had walked St. Cuthbert’s Way, and I’d become curious as to how pilgrimages differed from vacations, business trips, escapes, or educational trips. I was especially interested in the inner journey one makes on a pilgrimage. I read books about some of the pilgrimages people had taken, drawn especially to those who approached the spiritual journey with humor and curiosity. I decided to try to use the same approach in a blog about my travels.

But now when I reread those first blogs, I can’t find much humor. Like the novel, they still seem to me focused on the effects of my grief—physical problems, nasty thoughts and visions. What humor I find now sounds to me sarcastic.

Still, because I’m also writing about specific places—Jerusalem, retreat houses—I can also see the beginnings of my detaching, of stepping back, of broadening my horizons.

And that’s what writing these blogs over the next eight years has done for me. By focusing first on my various exterior journeys, and then going inward, I’ve given my grief more room to live in, so that it doesn’t dominate either my life or my writing. My grief over Laurie’s death is no smaller, but the landscape in which it resides has expanded to include not only a dozen countries, but also my family history and my geriatric journey as well.

Probably nothing has helped me better understand this interior landscape over the last eight years than joining two 12-step programs. Al Anon, the program for families and friends of alcoholics, and ACA, the program for adult children of alcoholics, have become like lenses on a pair of binoculars, helping me view the effects of my grief—especially fear, anger, and shame—as mountains that make the Eildon Hills look as level as pool tables.

I remember telling my Al Anon sponsor in one of our first meetings, “I will always feel at some level that I killed my daughter.” Even 25 years after Laurie died, I blamed my daughter’s death on my divorcing her mother two years earlier or by not divorcing her mother soon enough. I said that every year, right around Thanksgiving, I could feel my body chemistry change. For the next month or so, right up until the anniversary of Laurie’s death on December 23, I said, I never knew how I would react. Some years I was angry at everyone, some years I cried at anything remotely sad, some years I spent the months hiding from the world by reading mysteries. I said that I’d just accepted this response as the way it would always be.

And I remember my sponsor’s reply: “Okay. Maybe… Let’s see what happens.”

Through working the Al Anon program, especially Step Four, taking “a fearless moral inventory” of myself, I discovered that because I’d grown up in a family riddled with alcoholism, I’d been clambering up and down those mountains of fear, shame, and anger long before Laurie’s death. Fear and my need for what I thought was security had driven me into an unhappy first marriage. Shame and my need for respect had driven me into erecting any number of false personas. My need to deaden my anger had driven me into my own alcoholic behaviors. Using ACA, I learned about the long-term effects of growing up in an alcoholic family, while Al Anon gave me the tools to separate my grief for my daughter’s death from my fear, anger, and shame over losing her.

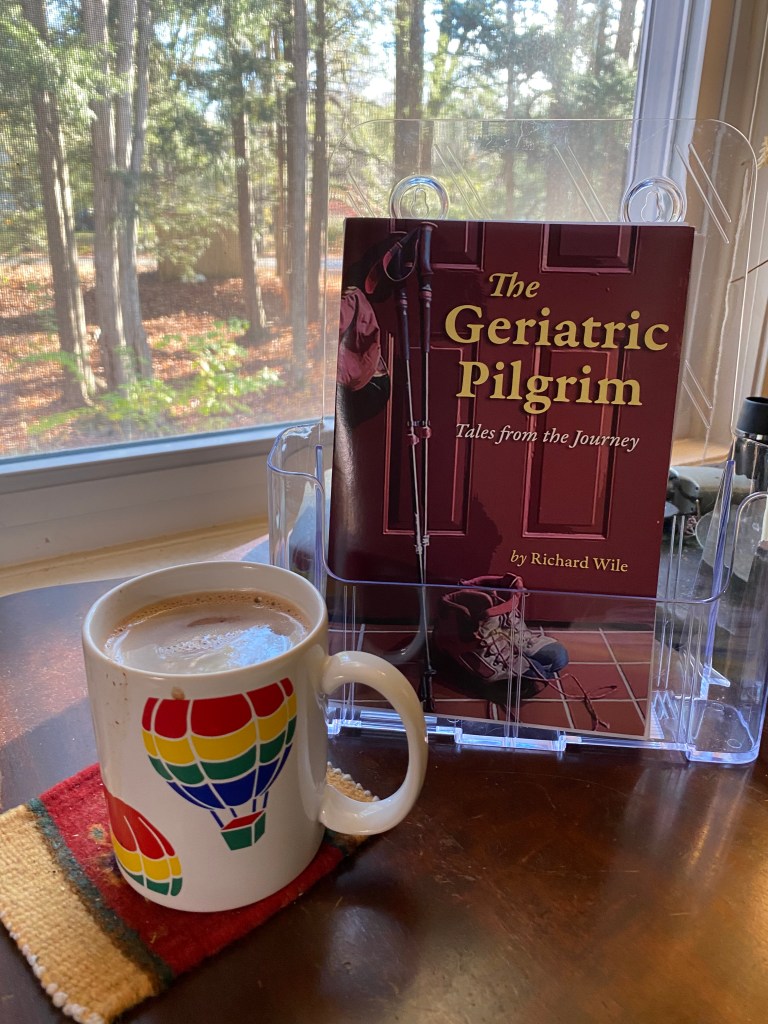

So that four years ago, I realized that I was enjoying the Christmas season—no tears, no angry outbursts at the baggers at the grocery store, no reading marathons. And as I was collecting fifty of my blogs to put together in my second book, The Geriatric Pilgrim: Tales from the Journey, I had to revise several blogs which had talked about how hard the Christmas season still was for me.

There’s also nothing like successful heart surgery for expanding one’s inner landscape. Only through a timely wellness checkup and the perspicacity of my PCP—“No, being out of breath is not normal. I want you to take a stress test this week!”—did I avoid another family disease: falling dead of a heart attack. Only because of what I’ve called in these blogs “grace” am I’m still here. Only through grace am I grateful for the life I’ve lived, even for those demanding hikes over mountainous landscapes.

All of which is worth celebrating. If not with paper hats and party horns, at least with a cup of hot chocolate.

Cheers!

# #