#

Perhaps it’s because I turned 80 this year. Maybe it’s because this summer has been hot and muggy. Whatever the reason, I’ve found myself more aware lately of my vulnerability. Walking in the woods these days requires changing into insect-resistant clothing because of ticks; on walks, working in the garden, I need to be sure to bring water with me or I get weak and dizzy; after heart surgery, I need to keep checking my fancy watch to make sure my heart rate doesn’t get much over 120 bpm. I’m tripping more often and have removed several rugs from our house. Earlier this year, I fell in my garden and only by grace/luck/whatever did I miss cracking my head on a rock by about 6 inches. And on a recent hot day, I was mulching my pumpkins, felt weak, saw that my heart rate was 145, sat down, and couldn’t get up. Fortunately, I had my water, and was finally able to get home after a half-hour or so (whereupon I had a 1½ hour nap).

I don’t like being this vulnerable, probably because I’ve spent a lot of my life trying to avoid showing vulnerability. As a boy in a small New England town in the 1950’s, I learned vulnerability was for sissies. Never ask for help; never let anyone see you cry. In high school, I learned success, whether on the basketball court or getting Suzie’s bra off, was a matter of will power. Mind over matter.

But these days, I find that what I mind doesn’t seem to matter. Which is why I’ve made a pilgrimage through the internet in search of something good to feel about vulnerability. At first, I didn’t have much luck. If you google the word “vulnerable,” most of the definitions have negative connotations: “capable of or susceptible to being attacked, damaged, or hurt; open to moral attack, criticism, temptation, etc.”

Still, looking up “Articles on Vulnerability,” I found advocates. Researcher and storyteller Dr. Brene Brown writes, “vulnerability is the core, the heart, the center, of meaningful human experiences.” Others write that vulnerability allows us to be authentic. It can bring a sense of closeness and fulfillment. It can bring about more honesty, more trust. Brene Brown again: “Vulnerability is the birthplace of innovation, creativity, and change.”

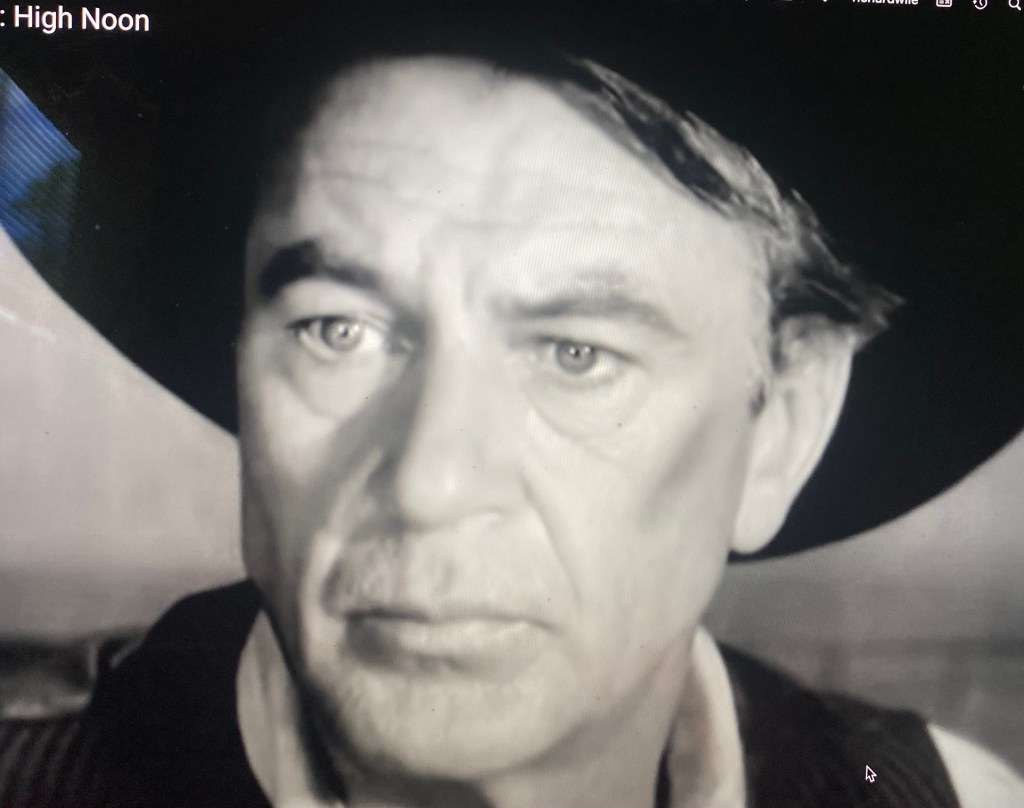

As synchronicity would have it, as I was reading about vulnerability, I was finishing the book, High Noon: The Hollywood Blacklist and the Making of an American Classic by Glenn Frankel. Which led me to watch for probably the tenth time, the movie on which the book was based. In case you’ve forgotten the plot, former marshal Will Kane (Gary Cooper) is preparing to leave the small town of Hadleyville, New Mexico, with his new bride, Amy (Grace Kelly), when he learns that local criminal Frank Miller has been set free and is coming to seek revenge on Kane for turning him in. When the marshal tries to recruit deputies to fight Miller, he finds the town’s people have turned cowardly. His wife, a Quaker opposed to violence, doesn’t understand why her new husband feels he must stay, so she decides to leave town. When the time comes for a showdown, Kane must face Miller and his three cronies alone.

This time, when I watched the film, I was aware of how the writer, Carl Foreman (who was being investigated for having been a Communist and who saw himself forsaken by people he thought were his friends), and the director emphasize Kane’s vulnerability. Through closeups of an aging Gary Cooper’s face, we see his fear, and scene after scene of overhead camera shots of his walking alone up and down what looks to be a deserted town show his smallness. Meanwhile, Tex Ritter is singing: “Do not forsake me, O my darlin’.”

Well, his darlin’ doesn’t. Amy comes back to help Will kill those nasty bad guys, and, after throwing his marshal’s badge at the yellow-bellied citizens of Hadleyville, Will rides off with his wife into the afternoon sunlight.

But although law and order triumphs in the end, the movie apparently infuriated traditionalists, like movie hero John Wayne and director Howard Hawkes, who said he didn’t “think a good sheriff was going to go running around town like a chicken with his head cut off asking for help.” So, Hawkes and Wayne made the western, Rio Bravo. In this movie, gunslinger Joe Burdette kills a man in a saloon, and Sheriff John T. Chance (John Wayne) arrests him. Before long, Burdette’s brother, Nathan, comes around, threatening that he and his men are going to bust his brother out of jail. Chance decides to make a stand. Does he ask the townsfolk for help? No way. “They’ll only get hurt,” John Wayne growls.

Meanwhile, unlike Will Kane’s wife, Chance’s love interest (Angie Dickenson), refuses to leave town. As the time for the showdown nears, she tells Big John, “You better run along and do your job.”

The message here seems to be that real men don’t need to ask for help; they inspire loyalty. Other reinforcements arrive: Dude, the town drunk, an old cripple named Stumpy, and a baby-faced cowboy, Colorado Ryan. Rather than showing fear as they await the arrival of the bad guys, they sit in the sheriff’s office making wise cracks and singing songs. After winning the inevitable shootout, they all stay in town to sing and crack more jokes with the lovable town’s folk.

In the face of danger, real men don’t ask for help, the movie proclaims. Real men don’t show fear. Real men sing and tell jokes.

Maybe it’s a sign of the times (my times, anyway), but I admire Will Kane, who overcomes his age, his fear, and his despair to uphold his principles, more than I admire John T. Chance who doesn’t seem to have a vulnerable bone in his body. I realize that thirty-five years ago, after my daughter Laurie died, still thinking that will power solves all problems, I tried to avoid asking for help, and how the resulting anger almost tore me apart, until, exhausted, I finally surrendered my will to a god I didn’t really believe in. Only then was I able to feel relief, and eventually even experience moments of joy, an emotion I’d never felt before in my life because I’d been too concerned with not being vulnerable.

Brene Brown and others go so far as to say that vulnerability is a sign of courage and strength. I can see that. To be vulnerable, I need to have a strong sense of self. I have to be honest about what I can and I can’t do, and I have to be honest with others, even if it means being rejected. I need to stop trying to prove myself. I must own my past mistakes, make amends to others, and move on. I have to be able to face difficult emotions, especially these days, about my diminishments, dying, and death. I must continue to ask for help and accept it.

And I damn-sure need to wait until cooler weather to mulch pumpkins.

# #