#

Last Palm Sunday, Mary Lee and I were supposed to begin a two-week retreat at a monastery in the hills of California. We’ve been going on retreats now for thirty years and I was eagerly looking forward to having more silence, being more aware of the world, doing more reading (I’m on a Buddhist kick right now), drawing closer to God of my not Understanding. Then, two weeks before we were supposed to fly to San Francisco, we received word rockslides had closed the roads, and that the monastery won’t open again until at least May.

So instead of flying across the country on Palm Sunday, we spent the day encased in ice.

The previous evening, thanks to a day of snow changing to freezing rain, we lost power. That Sunday, we cooked oatmeal on top of our gas stove and wrapped in blankets in front of our gas fireplace. While the ice bent the trees and bushes lower and lower, Mary Lee and I read the Palm Sunday service from the Book of Common Prayer, wondering, along with the Psalmist, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me.”

For the next day and a half, we ate beans and rice, read, played Scrabble and cribbage, drove around the neighborhood to charge our phones, and finally gave in and stood in line at a restaurant in another town for breakfast.

All in all, it wasn’t bad. Still, it’s hard for me to find much nice to say about ice.

I like ice cubes in my water. I use ice packs to help the bursitis in my hips. Some ice sculptures are pretty. I’m glad to have a freezer in my refrigerator to preserve food. But that’s about it. When I used to go skating, I’d divide my time between flailing my arms to keep from falling and lying prone on the ice when I did. The one time I went ice fishing, I was days warming up.

Ice has all kinds of nasty connotations. It can mean frigid, as in sexually inadequate. It can mean unfriendly, reserved, aloof, rigid, inflexible. Fear sends icy chills down our spines. We hear about the icy fingers of death.

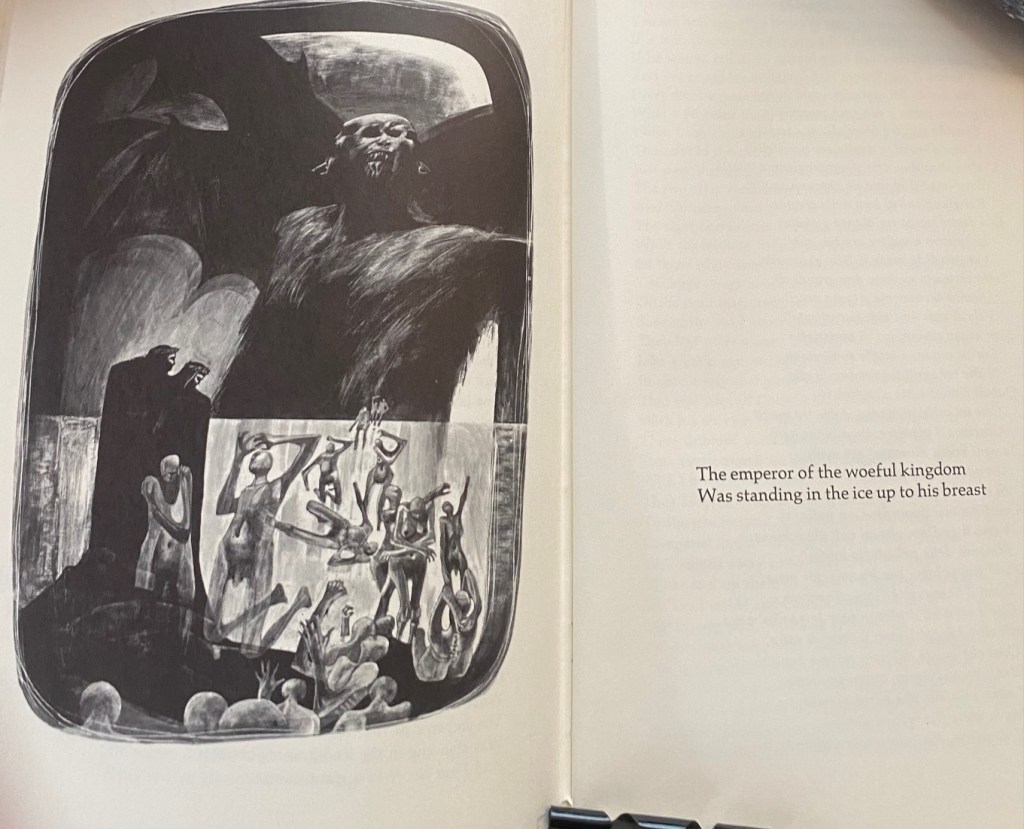

Speaking of death, while Hell (which is where some of my Fundamentalist friends tell me I’m going to go when I die) is usually pictured as a place of fire and brimstone, in Dante’s Inferno, the center of Hell is a vast lake of ice, in which Satan, along with sinners who committed treason and betrayal—such as Brutus, Cassius, and Judas—is incased.

Makes sense to me. Ice is cold. Ice is heavy. (The reason we lost electricity was because ice-laden trees fell on power lines). Ice prohibits movement. During the most hellish part of my life, after my daughter died, I couldn’t get warm. I felt as if I were carrying a 20 cubic foot freezer on my shoulders. My body was rigid and tense. Only after I’d had two or three large tumblers of scotch did I feel as if I were thawing.

And yet. For someone who dislikes ice, I realize that one of my tendencies is to want to freeze experiences and beliefs, preserve them the way we preserve meat and vegetables.

After those hellish first years when Laurie died, my life began to get better. I thought I was learning to live with loss. But five years later, at this time of year, it was as if my daughter has died all over again. I plunged back into rage and tears. I spent evenings drinking my tumblers of scotch (or maybe it was Wild Turkey 101 proof, at this point), going through old photograph albums of the two of us and listening to Laurie’s old tapes of Tracy Chapman and the Grateful Dead. The only difference was that those I was most angry with were people who talked about their own grief. I remember being at a retreat at a monastery in Cambridge, Massachusetts where a woman talked about almost losing her son in an automobile accident. A spasm of rage surged though me. I thought, What are you moaning about? He’s alive, isn’t he?

Then on Easter Sunday after this retreat, I heard a sermon based on the Gospel of Mark’s account of the Resurrection, which, unlike the other gospels, ends with Mary Magdalene, Mary the mother of James, and Salome, fleeing from the empty tomb, “for terror and amazement had seized them; and they said nothing to anyone, for they were afraid.”

Why fear, asked the preacher. Well, there might have been a lot of reasons—fear of soldiers, fear of grave robbers—but he also wondered if it wasn’t human nature to fear the unknown, to become used to, even comfortable with, our lives even if they’re full of pain and suffering. We prefer what we do know to what we don’t.

And I realized that over the years since Laurie’s death, I had grown comfortable with my image of myself as GRIEVING PARENT; I had made Laurie’s death MY STORY, trying to preserve memories of her, as in the old photograph albums I’d been perusing. And if anyone else had a similar story, I felt threatened.

In other words, I was trying to freeze my sense of myself and Laurie rather than let them evolve, flow. I wasn’t angry about the death of my daughter, I was angry at the possible death of my grief, thinking it was grief that was keeping me close to her.

That Sunday afternoon, sitting in Harvard Square amidst cigarette butts and pigeons, looking up at the sycamores and the brick buildings, listening to voices babbling in a half-dozen languages, I tried to focus on my daughter in the present moment. I don’t know where you are, Kid, I remember praying, but at some level I know you’re fine, and I want you to know that I love you.

And the sights and smells and noises of the Square seemed to fade and I felt a hand on my shoulder, and I knew it was Laurie’s.

I don’t care whether that hand was from another dimension or from my imagination. What I do know is that the great spiritual traditions are right: love transcends death. That is, if you don’t try to freeze it like leftover meatloaf.

But I’m still learning. Working a 12-Step Program, I’ve discovered traits that I developed to survive growing up in an alcoholic family—judgmentalism, people-pleasing, perfectionism—traits which no longer serve me, but have, in essence, remained frozen, damaging my relationships with others.

And I’m wondering if I may be trying to freeze my retreat experiences, and that Life, the Universe, or God of my not Understanding isn’t telling me by having this retreat in California canceled that I need to let the retreat experience—the silence, the awareness, the reading, the closeness to God— flow into my everyday life, here at home, even in the middle of an ice storm.

#