#

Besides dealing with a decaying body and a deteriorating mind, one of my biggest challenges these days is to keep from living in the past. (And I’m sure the two struggles are connected: of course, I want to recall when I could leap tall buildings in a single bound.) It’s so tempting to spend my days reminiscing with old classmates via email or Facebook, watching “American Bandstand” on YouTube, and replaying 65-year-old high school basketball games.

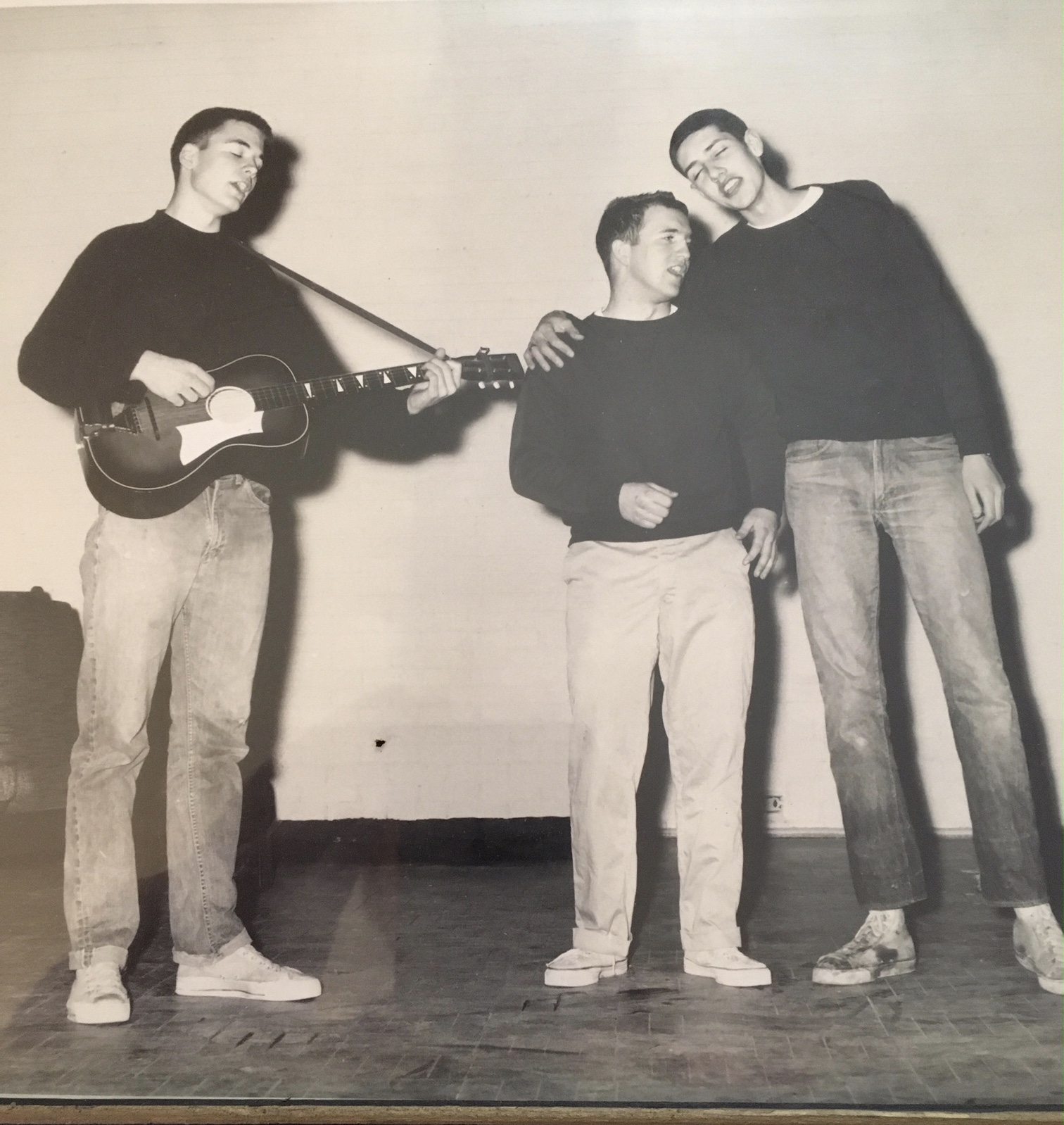

This last month has been especially challenging. May began at the history center in the town in which I grew up with a program that my oldest friend (going back to the first grade) and I spent the winter planning: “Yarmouth [Maine, for those of you reading this in Singapore and elsewhere], 1955-1962: Times of Change.” We wound up with probably thirty people there who’d grown up in town during those years, bathing in the warm waters of nostalgia, as we talked to newer residents about how Yarmouth changed during that time from a low-income community of shops and small factories to a bedroom-by-the-sea for urban lawyers, doctors, and bankers. A town we kids roamed at will because everyone looked after us—where the local telephone operator would call my classmate Barbara’s house at 3:30 in the afternoon (because she knew Barbara got out of school at 2:30 and would stop at the drug store for a coke, so that’s when she’d get home) to tell Barbara that her mother would be late and that she should turn the oven on 350° and put the roast in at 4:00. (Who needed cell phones?)

Later in the month, as my brother and sister and I cleaned off stones and planted impatiens in our family cemetery plot for Memorial Day, we swapped memories of Mom and Dad and our grandparents. (Amazing how different our recollections are!) Later that week, I went with my wife, Mary Lee, to her 55th college reunion, and for three days listened to other people’s stories about their pasts. Throw in a dream in which I ran into my ex-wife—who died eight years ago—dressed in a white karate gi (still trying to work out the symbolism there), and I’m starting to sink beneath these waves of nostalgia.

I need to get out and open my eyes. Stop looking at what’s behind me and start looking at what’s around me—what’s new. I decide to check out this year’s garden. Besides, I need to put in my tomato seedlings.

It’s a beautiful June morning and the world is new. The apple blossoms and rhododendrons are in full bloom, the air smells of lilacs, and the breeze is fresh. The world is spring green: the grass hasn’t yellowed, the leaves aren’t chewed, and the caterpillars haven’t yet built their ugly tents in the trees.

I put my seedlings and watering can and trowel in the car, drive up and park on the power line road between our community garden (which I wrote about a few years ago: https://geriatricpilgrim.com/?s=Up+to+the+Gahden) and a wooded swamp, home to all kinds of birds, many of whom are singing their ever-loving hearts out.

I had no idea how many birds there are here until I got one of those apps this year for my phone that identifies birds by their songs. So, I check it: cardinal—yes, I know their pulsating whistles; song sparrow—makes sense, I see all kinds of them; gold finch and chickadee—ditto. But what’s a great crested fly-catcher? And a red-eyed vireo? They’re new, at least to me. Cool.

Turning to the garden, I think of the beginning of baseball season, when, no matter how poor a team’s prospects, there’s always hope for a championship year.

This year, I’ve got three raised beds, and—God willing; I haven’t planted it yet—a small pumpkin patch. The garlic I put in last fall is up, as are the peas which I planted on May 1st. I decided this year to stake them with some of the branches that came down from last winter’s storms—the first time I’ve ever tried that, and it seems to be working: the peas are grabbing the branches with gusto. In another bed, I’ve got the usual two kale plants which will hold us until November, but for the first time, I’m trying a couple of eggplants and a purple pepper to see what happens. I’ve also planted bush beans for the first time in years. (Mainly because last year, I almost killed myself stringing pole beans, and vowed never again.)

I wave to Karen down the way who’s working on her bee garden. She’s also building a new compost bin, for which I need to thank her.

But first, let’s get those tomato seedlings in.

The sun is warm. I take off my outer shirt and begin raking the bed where I’m going to transplant my tomatoes. I love the smell of the fresh dirt (apparently, it triggers the release of serotonin in the brain—at least that’s what I read somewhere) which makes me want to sing. And because the other night I watched a music documentary on Paul Simon, I serenade the birds with “50 Ways to Leave your Lover”—

You just slip out the back, Jack

Make a new plan, Stan

You don’t need to be coy, Roy

Just get yourself free—

The really neat thing about the documentary was it focused on Simon’s newest album of songs, many, if not all of them, as I recall, coming to him in a dream. And if at the age of what, 83?, he can still be creating new work, even though I guess he’s now deaf in one ear, then I, at 81, can, too, despite my various diminishments.

I dig six holes and put a little of Karen’s compost in each one. I find myself slipping again into the past: the summers in high school I used to work in a garden and the big garden I had during my first marriage. Cut it out! I think, and then decide, No, let’s use those memories as compost, fertilizer to help me grow.

Which would be more inspiring if my back didn’t already hurt from this minimal exercise. From my other garden bed, I grab my new kneeler and bench combination, which I bought this spring, and kneel on it to put the tomato seedlings into the dirt and the compost, which gets my hands dirty and the rest of me feeling clean. Then, I put collars that I’ve made from plastic medicine cups around the seedlings to protect them from cutworms, and, using the metal arms of the bench to get myself off my knees, rise to get my tomato cages from last year. Finally, I give my little darlings a drink to get them on their merry way.

Feeling accomplished, I sit down on the new iron bench with the “Welcome” sign that someone—probably Doug, who, along with Karen oversees our community garden—has donated. I think about how I still rely on community as much as I did when I was a kid all those centuries ago.

Looking up, I follow an exhaust vapor trail in the blue sky until I see the sun flash on a plane, high in the sky, probably starting its descent into Boston. I imagine flying to new countries and seeing new vistas and new people.

But right now, right here, there are plenty of new things going on, thank you very much.

# #