#

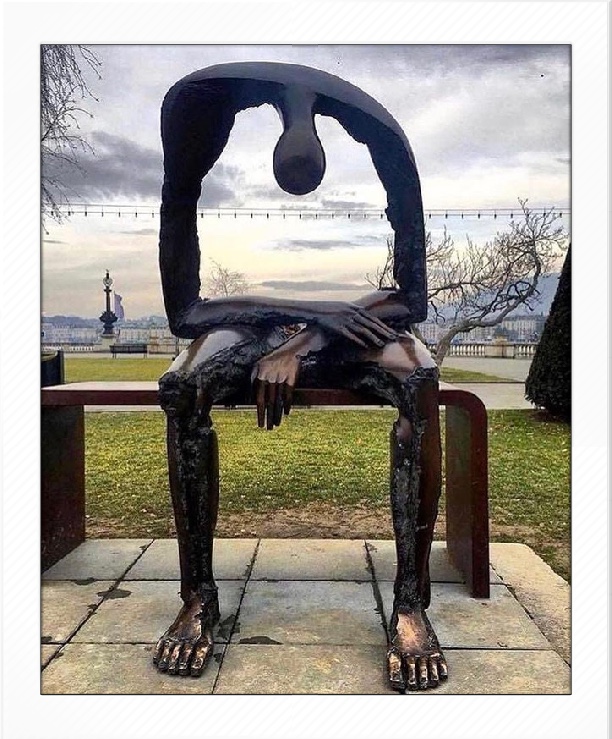

Gazing at the figure, I felt a physical reaction, a shiver, or perhaps more like the quiver of a struck bell. And I guess I wasn’t the only one who resonated to Romanian artist Albert Gyorgy’s “Melancolie”: the sculpture went viral on Facebook a few weeks ago. I wasn’t surprised that many comments came from viewers who’d suffered a great loss. A fellow grieving father responded: “We may look as if we carry on with our lives as before. We may even have times of joy and happiness. Everything may seem ‘normal.’ But THIS, ‘Emptiness,’ is how we feel … all the time.”

Later that same week, I mentioned to an old friend that the hole left in my heart by the death of my daughter would never go away. He seemed surprised and upset. “I had no idea,” he said. “I thought because you’re a Christian, your faith would sustain you. I feel sorry for you.”

No, I wanted to say, don’t feel sorry for me. My faith does help me. My life isn’t sad. My life is in some ways more joyful than it’s ever been. I continue to have a close relationship with Laurie. I—

And as I felt myself thrashing about, frustrated at not having the words to describe what it’s like to lose a child, I realized what an intricate and perplexing landscape this emptiness through which I journey really is.

There’s the idea of emptiness as Void, empty of meaning. It’s a frightening place. When my ex-wife phoned me with the news that what we’d always thought was a harmless sebaceous cyst on the back of our daughter’s head was malignant, I felt the ground opening under my feet. I remember needing to grab on to the counter I was standing beside. Mary Lee has since told me that when I picked her up at school later that day and she opened the door to the car, she felt an icy emptiness even before I told her the news.

The title of the sculpture, “Melancolie,” or melancholy, refers back to medieval medicine and to one of the four “humours,” black bile, thought to cause what we today call depression. This, too, is a kind of emptiness, at least when I look at some of the therapy websites that define emptiness as “a negative thought process leading to depression, addiction…”—both of which I’ve stumbled through since Laurie died.

But over those same years, I’ve also found that emptiness can be something to cultivate rather than cure.

My first readings about emptiness were from existentialists like Albert Camus, who saw meaninglessness as a reality of life, but who posited that we can and should create our own meaning. From there, I dabbled in Buddhism, where Emptiness is a central precept. But as I understand it, Buddhists do not believe life is meaningless; rather, that our images of ourselves as separate, independent entities don’t exist: they’re delusions, empty of meaning. When we can understand this meaning of emptiness, we realize that we are part of what the Buddhist monk Thich Nhat Hanh calls “inter-being,” which is the basis for wisdom, bliss, compassion, clarity, and courage.

Then, as I’ve written about before in these blogs, I learned a form of Christian meditation called “Centering Prayer,” which is based on “kenosis,” or “self-emptying.” As Saint Paul wrote in Philippians: Jesus “emptied himself, taking the form of a slave ….” Notice how many of the parables in the Bible advocate giving up everything, whether it’s Jesus telling the young man to give up his money and possessions and follow him, or the Good Samaritan giving up his money and time to minister to the man who’d been beaten and robbed, or the servant condemned for burying his one Talent.

And it was through practicing kenosis—entering into the emptiness I felt after Laurie died, giving up my image of myself as grieving parent—that I was able to feel Laurie’s renewed presence in my life. (For more on my experiences with Centering Prayer, see https://geriatricpilgrim.com/2016/06/)

Lately, I’ve been working a 12-Step program based on surrender, which as a speaker I heard recently said, “only happens when there’s nothing left.” Only when circumstances force you to see that all of your props, your addictions, have not only proved worthless in giving you what you need, but are actually keeping you unhappy, is it possible for you to give them up, empty yourself of them.

And yet. No matter how much I read about the subject, how often Laurie’s spiritual presence fills my emptiness, my daughter’s physical absence burns like an amputation. I will never have the chance to watch her face grow more interesting as it ages, never watch her take up a vocation, fall in love, perhaps have children.

And maybe that’s the price we pay for loving someone. A friend of mine who lost her husband a year ago recently sent me the following quotation from Dietrich Bonhoeffer, German Lutheran pastor and theologian:

Nothing can fill the gap when we are away from those we love, and it would be wrong to try to find anything. We must simply hold out and win through. That sounds very hard at first, but at the same time, it is a great consolation, since leaving the gap unfilled preserves the bonds between us. It is nonsense to say that God fills the gap. He does not fill it but keeps it empty so that our communion with another may be kept alive, even at the cost of pain.

So, emptiness for me is another landscape through which I pilgrimage—four steps forward, three steps back, two steps side-ways, circling, backtracking. Sometimes the views are bleak and dismal and the path is strewn with the rocks and roots of depression and addiction, but more and more often these days, as I’ve surrendered my seventy-year-old resentments at people long gone from my life, my judgmentalism, my shame over not being perfect, I’ve seen some magnificent vistas, felt fresh air tickling what little hair I have left, heard birds singing hymns of grace.

# #