#

Over the past 30 years, I’ve made many retreats to monasteries. The silence, punctuated by worship several times a day, slows me down, increases my awareness, and keeps me centered. All of which have helped me live comfortably during this last year of COVID-enforced isolation.

But as much as I love monasteries, I’ve never had any desire to be a monk. There’s the celibacy thing, for one thing, but also the fact that, at least in the monastery I’m most familiar with, the Brothers clean out their cells every year, discarding everything but the bare essentials. As one Brother explained, “Refraining from possession helps us remember the transient nature of earthly life.”

Well, I’ll admit it. I want my possessions. The room in which I’m writing this is full of them. I have bowls of stones from the various pilgrimages Mary Lee and I have made, a hat covered in hat pins from states and countries I’ve been to, and a budding collection of banjos. I also have random things: a wooden plate made by my father, a few joke books written by an old friend, now deceased, a pencil holder that used to belong to my father-in-law…

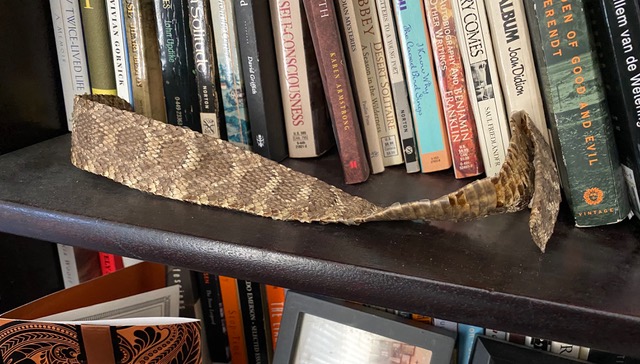

And a snakeskin.

Almost 60 years old, the skin rests on my bookcase, brittle, brown, and bent. When I pick it up, it crinkles like old parchment. Some of the translucent scales underneath, looking like fragments of old scotch tape, have fallen off (another came off now). I can’t think of anybody who’d want the damn thing except me. And I wouldn’t part with it for $1000.

As I run my fingers over the mottled brown and yellow skin, the years fall away and it is the summer of 1963. I am slowly coming down a steep slope of something between a hill and a mountain in the Payette National Forest in Idaho. Below me is the third fork of the Salmon River. (Often called “The River of No Return.” If you can, check out the 1954 movie by that name starring Robert Mitchum and Marilyn Monroe.) As I descend, picking my way through blackened rocks and burned shrubs and grass, I begin to encounter small groves of Ponderosa Pine and Douglas Fir, which I check to make sure aren’t smoldering. But they’re fine. The fire didn’t get down this far.

I’m working on a Hotshot Crew based in McCall, Idaho, a small touristy town on the edge of Payette Lake (something like 5,000 people and eight bars) about thirty miles from here. Our crew is a regional crew, which means we’re flown to any state in the upper western United States that has a large forest fire. The term “hotshot” describes those who work on the hottest part of a forest fire. Our primary job is to dig a fire line around the fire. We have a crew of eighteen, plus a crew chief, Paul, an assistant crew chief, Tex, and a scout, Dave Bodley, “Bo Diddly,” we call him, a bear of a guy who goes ahead with a chain saw, cutting down limbs, clearing a path through fallen trees. Then, we follow in a line as close to the fire as we can get. Twelve of us carry pulaskis, a tool which combines an axe and a hoe in one head on a three-foot handle, to scrape the forest duff and chop roots.

The remaining six of us have shovels to scrape and widen the fire line to about three feet or more. The idea is to cut a fire line and walk at a steady pace at the same time for as long as needed, sometimes for up to twelve hours. Once the fire is contained, we go into the burned areas and put out individual hot spots by scraping the burning coals from the trees or shoveling dirt on the flames or just digging smaller fire lines and letting the fire burn itself out. Then, when the fire’s under control, we let the locals mop up what’s left and head back to McCall.

Except this time we’re the locals. The Payette is our own National Forest, and after we contained the blaze, I volunteered to stay behind with Tex, Birddog, and Mike for two or three days to make sure we didn’t miss any remaining fire.

So we have two or three days to hike up and down the hills looking for smokes, swim in the chilly waters of the Salmon River, have Pulaski throwing contests, play poker around a campfire, and hunt rattlesnakes. These rocks and ravines are home to all kinds of snakes who like to come out in the afternoon and sun themselves, and I want to catch a rattler.

Despite the fact that this is my second summer on the job, I’ve never run into one. Part of our training has been to learn what to do if bitten and I have a snake-bite kit in my backpack, but so far, all I’ve seen are bull snakes, who look like the Northern Pacific Rattlesnakes that live here, but don’t have the rattles.

Then, on the ground ahead of me in front of an opening in some rocks, I see a snake. I inch my way closer, but I still can’t tell what kind it is. In addition to having rattles, rattlesnakes’ eyes are more like cat’s eyes than those on a bull snake, but I’m not near enough yet to tell.

When I’m maybe a couple of yards away, my foot crunches some gravel. Within seconds, the snake coils, raising its arrow-shaped head and tail. I hear the rattling. Without thinking, I take a giant step forward, swing my Pulaski over my head and drive it down through the snake, slicing it into three pieces.

The smallest piece is the head. I poke it with the Pulaski, noting its long thin tongue outside its mouth. I take the other two pieces to camp. Tex shows me how to skin them, and hang the skins up on a branch to dry in tomorrow’s sun. That night we have a rattlesnake appetizer (and yes, it tastes like chicken) to go with our canned Vienna sausages. Two days later, I take the largest skin, about 15” long, with me.

I know my life is transient—“like grass,” as the Psalmist says. Which is why I need to spend what’s left of it looking at more than the small grove of fir trees out my back window. Especially in this year of not being able to travel physically, I need a wider view. Of 10,000-foot mountains and a river full of cutthroat trout, bull trout, rainbow trout, mountain white fish, sockeye salmon, Chinook salmon, steelhead, smallmouth bass, squawfish, sucker, and sturgeon. Of guys from California, Oregon, Washington, Utah, Texas, Oklahoma, Nebraska, Utah, and Colorado, with names like Bo-Diddley, Birddog, Tex, Spankie, and Alfalfa.

A view that encompasses not only space but time: when I had a different name, “Froggie,” because of the way I hopped when I was first learning to dig a fire line; when I could dig that fire line for twelve hours and then walk another ten miles out to a cattle truck taking me to the airport; when I could flip a Pulaski fifteen feet and stick it into a pine tree. When the stars at night seemed to be so close that I could reach out and grab one any time I wanted.

All of which I can access by simply holding objects like a dried-up snakeskin in my arthritic hands. Suddenly, I am standing on the top of one of those 10,000-foot mountains, gazing over the vast landscape that is memory.

# #

You’ve captured the experience vividly in a short space here. Nicely done. The world has gotten very small this past year. I, too, am ready for a bigger view… Not sure where yet, but soon, I hope.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thnx, Jeff. I imagine some of those guitars have a story to tell…

LikeLike

This is the whole story of the snakeskin! I still say “No thanks!”

LikeLiked by 1 person

I really love this piece, Rick. Memory, nostalgia, the richness of life relived.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well done, Rick!

This piece was very interesting: great detail and drama. Your “voice” was clear throughout.

Although you didn’t explicitly mention it, the “exhaustion” of fire fighting spoke to me. Joe

PS. Did you ever bring the snake skin to any of your high school writing classes?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thnx, Joe. I think I did bring the snake skin in once. A lot of “Oooh, gross!” (Got some of that this time, too)

LikeLike