#

Recently, Mary Lee and I met her son and his family at a state park halfway between our respective homes for a rare face-to-face visit. After lunch, during which Mary Lee and I stood six feet from the picnic table, I pitched a plastic ball to my 8-year-old grandson who’s developing into a pretty good left-handed hitter. Both of us wore our masks. When the families left a few hours later, we gave each other “virtual hugs” and blew kisses.

As I was pitching to John, I started wondering how this pandemic will mark him, his sister, and their generation. Which led me to thinking about “defining moments,” those events that have transformed the political, cultural, and social landscape of our lives. From there, it was the blink of an eye to thinking about my own defining moments. The first one I thought of was President Kennedy’s assassination.

#

When I was eighteen, the speeches of John F. Kennedy were neon signs lighting my road to adulthood: “We stand today on the edge of a New Frontier” … “My fellow Americans, ask not what your country can do for you; ask what you can do for your country”… “Conformity is the jailer of freedom and the enemy of growth.” The man spurred my imagination. I decided I would live a life of adventure, passion and danger. After high school, I started traveling, first thumbing rides around the state, then around New England and New York. I entered the University of Maine’s forestry program, through which I found a summer job working on a hotshot crew out of McCall, Idaho, saving my country from forest fires and myself from conventionality.

The trail of the rugged individualist, however, turned out to be a difficult hike. While I might have loved working in the woods, I hated the class work and almost flunked out of college after my freshman year. Because I liked to read, I switched my major to English, but my grades remained low. I’d grown up in a small town where everyone knew me; I’d never learned how to meet new people. My mother was a controlling woman whose desire to protect her children kept me tied to her apron strings in ways I wouldn’t understand for fifty years. I watched former high school classmates join fraternities and sororities, disdaining them for being weak-spined conformists while at the same time envying their apparent happiness.

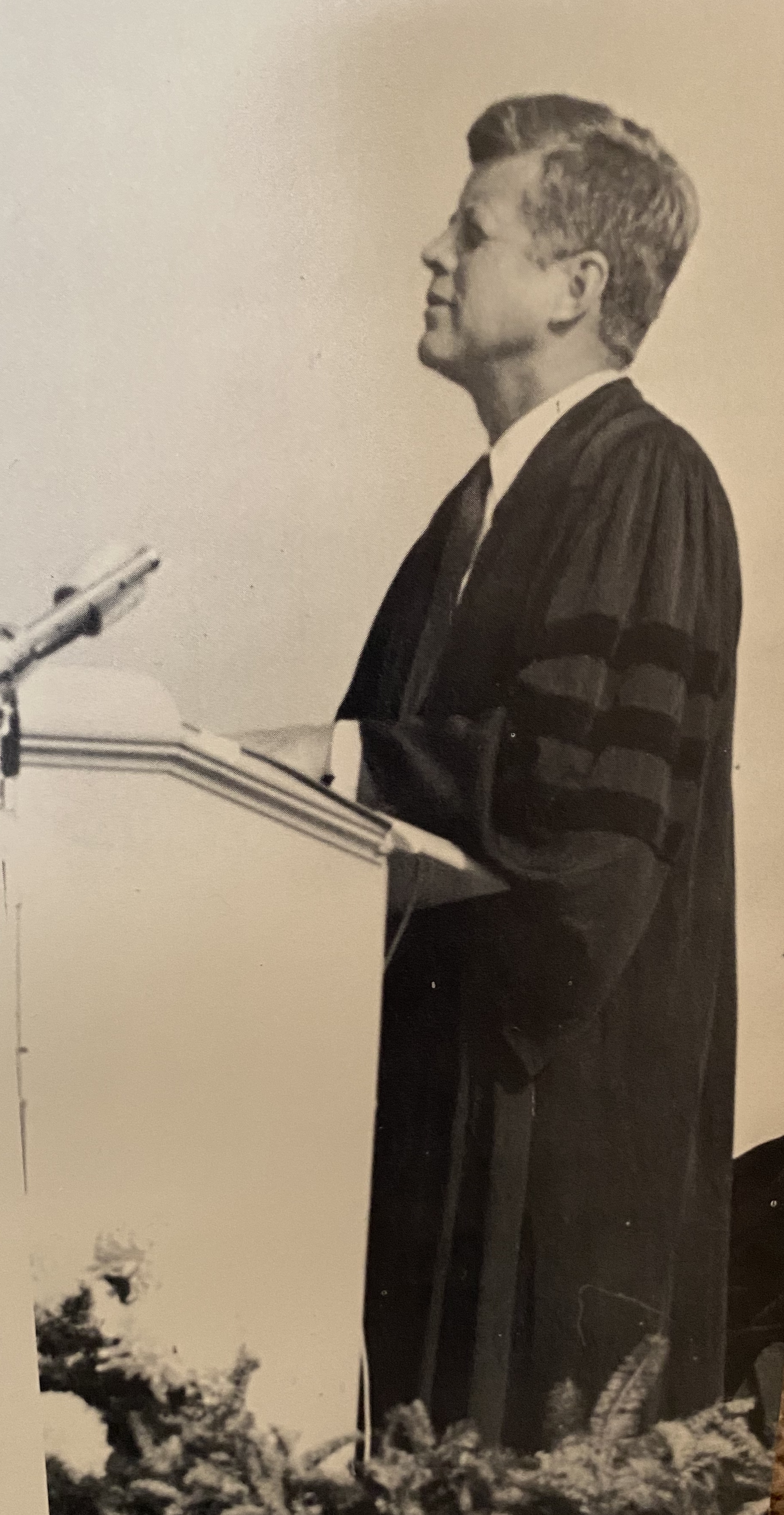

And then in October 1963, I watched President Kennedy descend in a helicopter’s whirlwind and walk bareheaded through the blowing dust of the track around the University of Maine’s football field like Apollo, his hair never moved. Standing in the shadow of the stands as October sunlight haloed JFK, his voice fanning my flicking dreams of fame, I decided to join the Peace Corps after graduation, then become a writer, with my picture on the cover of Time magazine for winning the Nobel Prize for Literature, dividing my time between Ernest Hemingway’s Paris, Jack Kerouac’s New York City, and an island off the coast of Maine.

#

A month later, I was leaving the Student Union when I heard a voice say, “Did you hear? Kennedy’s been shot!” I rushed back upstairs to a TV, arriving just in time to hear Walter Cronkite intone, “From Dallas, Texas, the flash, apparently official: President Kennedy died at 1 p.m. Central Standard Time.”

I spent the weekend sitting in the dark of my dorm’s television room, watching the arrival of the plane from Dallas to Washington bearing the President’s dead body … the closed casket draped in black crepe lying in the East Room of the White House … the horse-drawn caisson carrying Kennedy’s casket down Pennsylvania Avenue to the Capitol … gray figures marching to the steady beat of funeral drums into Arlington Cemetery.

#

After the burial service, I stuck a cigarette in the corner of my mouth and walked through the mist and fog and the almost empty campus. I tried to imagine myself as Kerouac’s Sal Paradise walking through a dying America.

Through the fog, I heard the voices the Kingston Trio, a popular folk group of the time, either their recording, or—more likely—a television retrospective on the Kennedy years:

Some to the rivers and some to the sea.

…

This is the new frontier.

This is the new frontier.

On the lawn by Sigma Nu Fraternity, the few remaining leaves of a maple tree hung like flags at half-mast.

I walked up a hill to Deering Hall, where I’d suffered through those forestry classes. I’d thought the one good thing to come out of that miserable year was the chance to fight forest fires out west, but now I realized how I’d never fit in. Most of the other guys on the crew were from rural southern or western towns and had never heard of Hemingway or Kerouac. Many were racists; most disliked the Kennedys. They could, however, play poker and the previous summer, I’d lost almost half the money I’d earned.

The mist turned to steady rain. I lit another cigarette and pulled the collar of my jacket around my neck. I suddenly knew I wouldn’t be going back to Idaho again. In another flash of awareness, I saw that in order to become a world-famous novelist, I was going to have to write a novel and I had no idea how to do it.

The cigarette tasted lousy and I flicked it on the sidewalk. I watched the red glow fade and smolder, along with my dreams of wandering the world, battling conformity, and winning the Nobel Prize.

I had not cried all weekend, but now I was sobbing. For the first time in my life, death was real.

#

Looking back, I can see myself crossing a different new frontier, the frontier of grief. And I think it’s these moments of grief—whether they be the Kennedy Assassination, the Great Depression, or our own personal tragedies—that define us.

So, how did Kennedy’s assassination define me?

I became cynical about politics and “great” men and women. I never joined the Peace Corps, never again looked to a political figure for any kind of guidance on how to live my life. Instead, I’ve found my inspiration from literature, philosophy, and spirituality. But even here, I’m suspicious of literary or spiritual gurus.

After three years of looking for adventure, I began looking for security, which at first, I thought meant love. A year after the assassination, I was engaged, and I married two days after graduating from college. In retrospect, it was a mistake to equate security and love. The marriage ended. But through a happy second marriage I learned love is its own adventure, more important to the world—my world anyway—than having one’s picture on a magazine or owning three houses around the globe.

And how will Coronavirus define my grandchildren? I don’t know how they will be scarred. They may become hypochondriacs, isolated behind their electronic devices, or huggers working to bring about a socialist revolution. All I can do is surrender my fears for their future over to the God-of-my-not-understanding, hoping these kids will discover before I did how it is love which defines us more than any historical moment.

# #

Thank you,, Rick, for yet another thoughtful moment leading me to reflect on JFK’s death andsome other happy and sad moments along the way.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dear Cousin Rick, This post has moved me to tears. Thanks so much for your insight and introspection. I will share with firends. Excellent commentary on the current state of our world. Bravo. Be safe and well, Cousin Emily

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thnx, Em. Peace be to you and yours. Rick

LikeLike

Nice blog

LikeLike