#

“There is no song more agreeable to the heart than the slow, even breath of a pilgrim learning to bless, and be blessed by, the mystery.” — Stephen Levine.

#

Mary Lee and I are training for our next pilgrimage. We’re increasing the length of our walks, trying to step up our pace, and climbing hills. It’s the climbing business that I especially need to work on. We didn’t plan for hills on our last pilgrimage, and I don’t want to make that mistake again.

Rarely a day goes by that I don’t curse the Monday afternoon in 1961, two days after the State Class L Basketball Championship (where, despite my solid performance, our team was crushed, 74-52), when I filched a pack of my father’s unfiltered Camels and spent the afternoon learning how to inhale and the next forty years trying to quit. Throw in two summers inhaling woodfire smoke as part of my job as a U.S. Forest Service hot shot crew member (wearing a bandanna over my nose and mouth to keep the smoke away and then taking a break to sit under a tree and smoke a cigarette or two), and you have my scarred lungs and “mild” COPD.

But I’m finding it’s possible to increase my lung capacity. The internet is full of video instructions in breathing for singers, saxophone and harmonica players, swimmers, and the rest of us just plain folks. My osteopath is a firm believer in breathing correctly and has given me exercises to make sure I’m using all of what lung capacity I have. I’ve recently added a breathing activity based on a type of exercise therapy called Feldenkrais. And I’m tramping up and down stairs and hills any time I get the chance.

Breath, I’m finding, is a great teacher. After being physically abused at her daycare center, our granddaughter struggles with anger issues. Her counselor’s office has a “breathing ball” which expands and contracts as our granddaughter practices taking ten deep breaths for when she gets mad. We should all probably have one. Research shows that a period of deep breathing causes blood pressure to drop and stay down for as long as thirty minutes.

I think the first times I ever paid any attention to my breathing were when I played sports. My little league coach, Frank Knight, told us to take a deep breath before getting in the batter’s box, and Mr. Beal, my eighth-grade basketball coach, told us to do the same thing as we stepped to the line to take a foul shot. Fast forward forty years, and my nurse is yelling, “breathe!” the first time I try to walk after bi-lateral hip surgery. These days, my scarred lungs let me know whenever I’m tense or self-conscious—about reading or playing my banjo in front of an audience, for example—and that it’s time to pretend I’ve got my granddaughter’s breathing ball and inhale and exhale deeply.

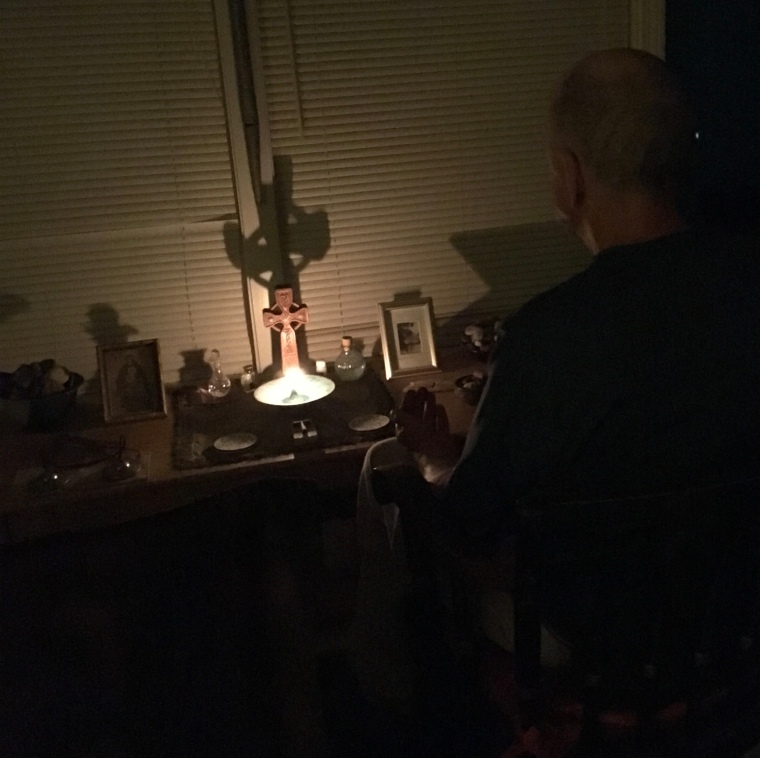

Using the breath in some way is the basis for almost every meditation practice I know. Breath is immediate and always there. Focusing on breathing brings us back into the present moment, whether it’s pranayama, a yoga tool for self-transformation in which one varies the length of inhalation and exhalation, or Buddhist practices like counting breaths and inhaling through the nostrils and exhaling through the mouth, or Christian Centering Prayer using mantras such as “Lord, Jesus Christ, have mercy on me” or “Breath of God, breathe in me” that follow the rhythm of our breathing, or the practice I’ve found in all three traditions of simply watching the breath without trying to control it.

Breath can be a constant reminder of our connection with the energy of the universe. Focusing on the breath helps me see myself as part of a world breathing its own rhythms: the ebb and flow of the sea, the waxing and waning of the moon, the inhalations of spring and summer and the exhalations of autumn and winter. I see my life as a kind of breathing: inhaling moments such first love, first teaching job, marriage, the birth of a child, first pilgrimage, the birth of grandchildren; exhaling houses I’ve left, an unhappy marriage, the death of my daughter and my parents, jobs I have retired from, and now, the death of old friends.

Trying to observe my breathing without trying to control it (which is really hard, by the way; I’m guessing I can come close maybe one day out of every four) helps me understand the mystery of Grace, which, like my breathing, is always flowing, continually feeding, repairing, sustaining, while at the same time taking away that which is unnecessary and wasteful. Whether it’s Grace or breath, I can control to some extent how much I take in, I can work on preparing myself to better use it, but I can’t hold on to it, and the only way to stop it is to destroy myself.

So, as I prepare for the next pilgrimage, breath is teaching me what I can do, what I cannot do, and what I can learn to do. It’s a kind of Serenity Prayer: “God grant me the serenity to accept the hills I cannot climb, the courage to know when to keep gasping up the ones I can, and the wisdom to know when to stop and catch my breath.”

# #

c

Hi Rick: Where are you and Mary Lee going next? I loved your modification of the Serenity Prayer: “God grant me the serenity to accept the hills I cannot climb, the courage to know when to keep gasping up the ones I can, and the wisdom to know when to stop and catch my breath.” Best~ Andy

>

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m a primary school teacher and I use the breathing ball for myself as well as for the children. We teaching lots of breathing games to the children and meditation. Thanks for the beautiful writing. 😀🌈

LikeLiked by 1 person