A few weeks ago, I made a pilgrimage to Mount Desert Island, where I once lived and worked, to attend a five-day contemplative retreat. During the first session, our facilitator asked us to share a particular concern we’d brought to the retreat with us. When it was my turn, I found myself saying I worried that during what is traditionally a time of hope, I’d lost hope in the future of this country. At almost 75, I said, I wasn’t that distressed about my prospects, but I worried about those of my grandchildren.

I also said that this time of year has always been a hard for me to be hopeful because my daughter died on December 23, 1988, and for the past twenty-nine years, the increasing darkness outside mirrors the increasing darkness inside of me as I recall the two months I spent living at a Ronald McDonald House, walking back and forth to the hospital to sit by Laurie’s side watching her grow weaker every day.

Since that retreat, I’ve been thinking a lot about hope and about Laurie, and as strange as it might sound, I’m finding the more I look back over the years since her death, the more hopeful I am for my grandchildren and for myself.

One of the questions I asked myself after Laurie died, was “How am I going to survive this?” Well, my pilgrimage through grief hasn’t been easy, for me or my family. I still stumble in anger, still get mired down in resentments. But looking back over the twenty-nine years, I can also honestly say that I have discovered grace and joy and a peace that, as the Christian Apostle Paul wrote, “passes understanding.”

I’m not entirely sure where this serenity has come from, but so far, I can think of four possible sources, four reasons to give me hope, four legacies I want to pass on to my grandchildren for their futures:

The Strength of Family. I grew up in a family scarred by alcoholism, abuse, and abandonment. Some of those wounds were passed on to me and my siblings, and I’m still in recovery, still realizing how this background has influenced my behaviors over the years, from my own addictions to my arrogant and judgmental attitudes. But the work I’ve been doing lately in my twelve-step program has also shown me that I’ve reaped the benefits from having two parents who overcame their own hideous childhoods, who loved me, sacrificed for me, and, above all, gave me some of my character traits I’m most proud of, including the strength to overcome the loss of a child.

I want to pass that strength on to my grandchildren.

The Dynamic Detachment of Nature. I’ve spent some of the most “spiritual” moments of my life struggling up mountains, sweating in deserts, snowshoeing in bitter cold, and peering through ocean fog. What makes these landscapes spiritual for me is that they make me feel small and insignificant. The ocean is going to break over the rocks no matter if I’m filled with joy or filled with grief; the sunrise will paint the clouds pink regardless of what happens in Washington. Yes, Nature is filled with death, disease, and violence, but even in death it teems with life. One of my favorite images from hiking Saint Cuthbert’s Way from Scotland to England is of a blown-down tree, its roots exposed. The tree’s branches have grown into four new trees rising from the decaying trunk. That force, that instinct to grow and blossom and bloom, drives, I think, all life.

I need to remind myself that force runs through my grandchildren, giving them the power to flourish, no matter what obstacles they’ll face.

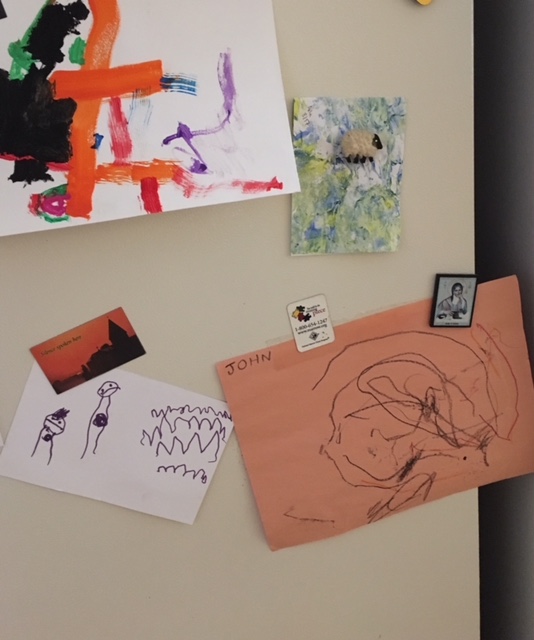

The Healing Power of the Arts. Before Laurie died, about the only writing I’d done was in my journals. I was an academic. My goal was to do more work for the College Board as a consultant. But after Laurie’s mother and I divorced, Laurie, who had also been focused on academic studies, swapped her L.L. Bean skirts and blazers for long sweaters and jeans, dyed a pink stripe in her hair, painted her fingernails black, and took up art, going to summer art programs, and planning to study art in college. After her death, I began going to summer writing programs, took early retirement from public school teaching, and went back to school for an MFA. Writing helped me identify my feelings, and became a way for me to harness my anger and my shame by writing a book and then revising it through God-knows how many rejection slips. More important, writing, like the banjo I wail on, like Laurie’s watercolor that hangs over my desk, reveals to me an essential order to what often seems, especially after a great loss, a chaotic and meaningless universe.

My grandchildren love to listen to stories, love to tell stories. It’s apparently natural for them to build and color and draw pictures. I want to nurture those instincts.

The Chuckle in the Dark. In A Grief Observed, popular theologian C.S. Lewis recorded his anguish over the death of his wife. Never intending his words to be published, he railed against God for the suffering and pain his wife had endured, and for the sorrow that was tearing him apart and demolishing everything he’d previously believed about God. Gradually, however, he experienced an “impression which I can’t describe except by saying that it’s like the sound of a chuckle in the darkness. The sense that some shattering and disarming simplicity is the real answer [to the mystery of suffering and death].” The retreat that I participated in a few weeks ago focused on the works of an anonymous 14th century writer who felt that the only way one could experience God was in what he called a “Cloud of Unknowing.” Since the loss of my child, my experience of God/my Higher Power/ the Eternal/Whatever has been through subtraction rather than by addition. I’ve lost all I ever learned about God, especially the idea that God is some compassionate Superman: all-loving, all-powerful, and all-knowing. And like C.S. Lewis, like the anonymous 14th century author we discussed, as I’ve lost those images of God, I’ve experienced an unfathomable serenity, one that has lasted this year well into the holidays.

I’m still not optimistic about the future of this country. I’ve read too much history about the rise and fall of empires not to feel that our nation is in decline, if not free-fall. But over the last few weeks I’ve discovered a difference between optimism and hope. Hope—for me anyway—is as much about the past as it is about the future. Hope looks back and grieves the reality of death, disease, decline, and destruction but at the same time, hope gives thanks for a life filled with the grace not only to survive but to thrive.

Which gives me hope my grandchildren will do the same.

# #

WELL SAID, RICK…THANK YOU…

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a wonderful reflection, your vulnerability enables me

LikeLiked by 1 person

Rick: I, too, have been very depressed about the future of our nation. If we can’t get rid of Trump, I do fear he will lead us to ruin. I wish I had your sense that there is some hope in the younger generation. We all need to find some reason to hope! I love the photo of the tree you saw hiking Saint Cuthbert’s Way with its roots exposed… Best~ Andy

>

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for your timely message, Rick. I also worry for the future of our 7 & 5-year-old granddaughters in the political and environmental climate in which we seem to be mired. You remind me to look at my own upbringing and where I’ve come to from it, and then at my granddaughters who have a natural resilience, intelligence, and creativity, and my hope is restored.

LikeLiked by 1 person